POPPLETON RECREATION CENTER

LOCATION: Poppleton, Baltimore, Maryland

YEAR: 2025

SIZE: 7,000 SF

CLIENT: Southwest Partnership

CONTRACTOR: Plano-Coudon Construction

2025 Urban Land Institute Baltimore Wavemaker Award

2025 AIA Maryland Design Excellence Award in Historic Preservation

2025 AIA Baltimore Social Equity Design Excellence Award

2025 Preservation Maryland Phoenix Rising Award

2025 Baltimore Heritage Award

Once celebrated as a “Play Machine,” the Poppleton Recreation Center was a vital hub for Southwest Baltimore before closing in the early 2000s. After more than two decades of vacancy, the 7,000 sf facility has been comprehensively renovated, restoring an architecturally significant late-modern structure while reestablishing a civic anchor at the heart of the neighborhood.

The design preserves the building’s distinctive identity—continuous ramps, exposed systems, and abundant daylight—while adapting it for contemporary needs. Upgrades include new mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems, full ADA accessibility with an added elevator, and safer, more transparent circulation. Flexible interiors now support after-school programs, computer labs, fitness and dance classes, and community meetings, while maintaining access to the adjacent pool. Exterior colors selected by residents, along with local murals and restored supergraphics, reflect Poppleton’s history and aspirations.

The renovation represents the first major public capital investment in the neighborhood in a generation. Once devastated by the “Highway to Nowhere” and decades of disinvestment, the Poppleton community led the vision for this project, ensuring the building responded to multigenerational needs. Partnerships among residents, nonprofits, faith-based organizations, and city agencies shaped both design and financing, making the project a true grassroots achievement.

Today, the Poppleton Recreation Center once again serves as a vibrant community hub and a symbol of resilience. By preserving its original character while adapting it for 21st-century wellness, the project demonstrates how architecture can operate as infrastructure for equity. It restores not only a building, but also the essential fabric of community life.

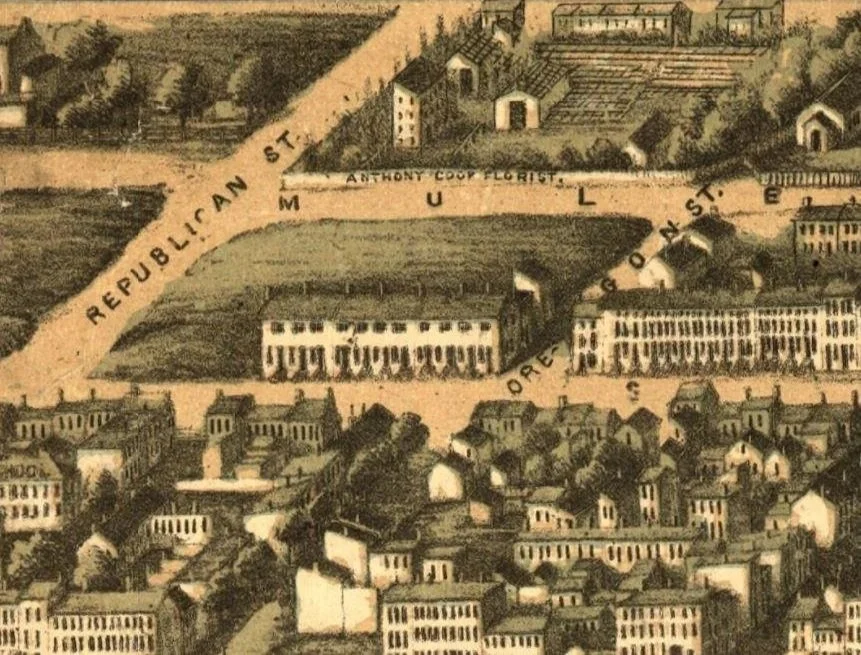

1870

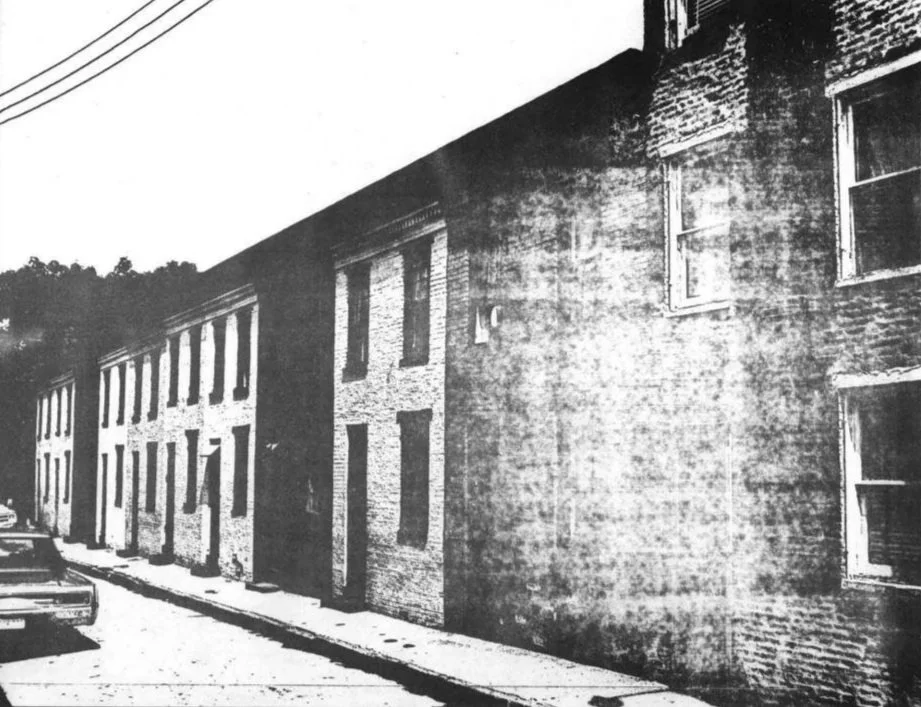

A historic row of houses built after the Civil War, originally intended to provide affordable housing for working-class African Americans. (CHAP Application)

The 1100 block of Sarah Ann Street, these two-story rowhouses are a rare example of intact, well-preserved alley houses. (Poppleton Area Study, circa 1978)

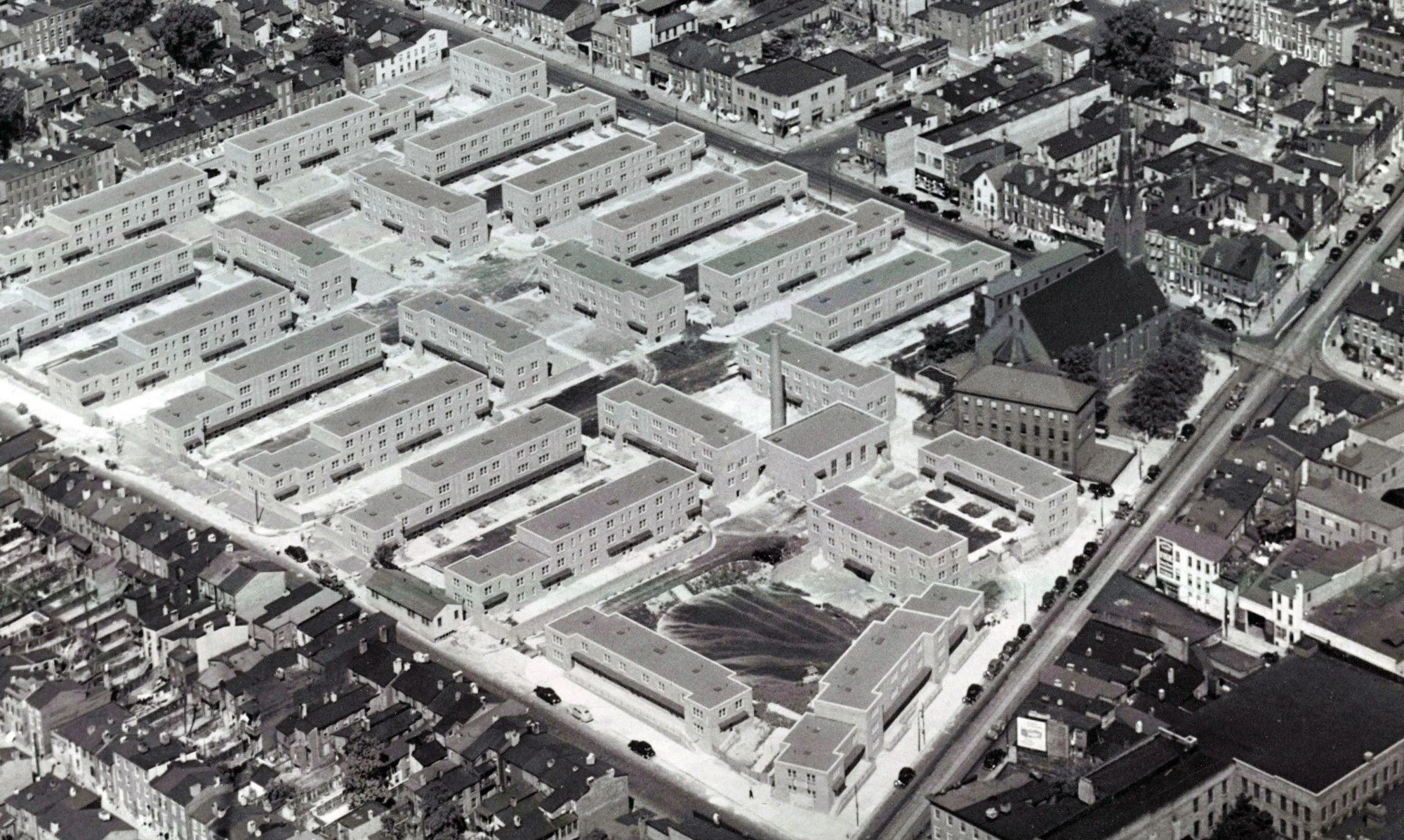

1927

Throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, West Baltimore neighborhoods were densely packed with working-class rowhomes. The future Poppleton Rec Center is indicated in red.

1940

Beginning in the 1930s, the City’s “slum clearance” efforts sought to reimagine Poppleton. Poe Homes (shown here during construction) opened as the first public, but segregated, housing complex in Baltimore.

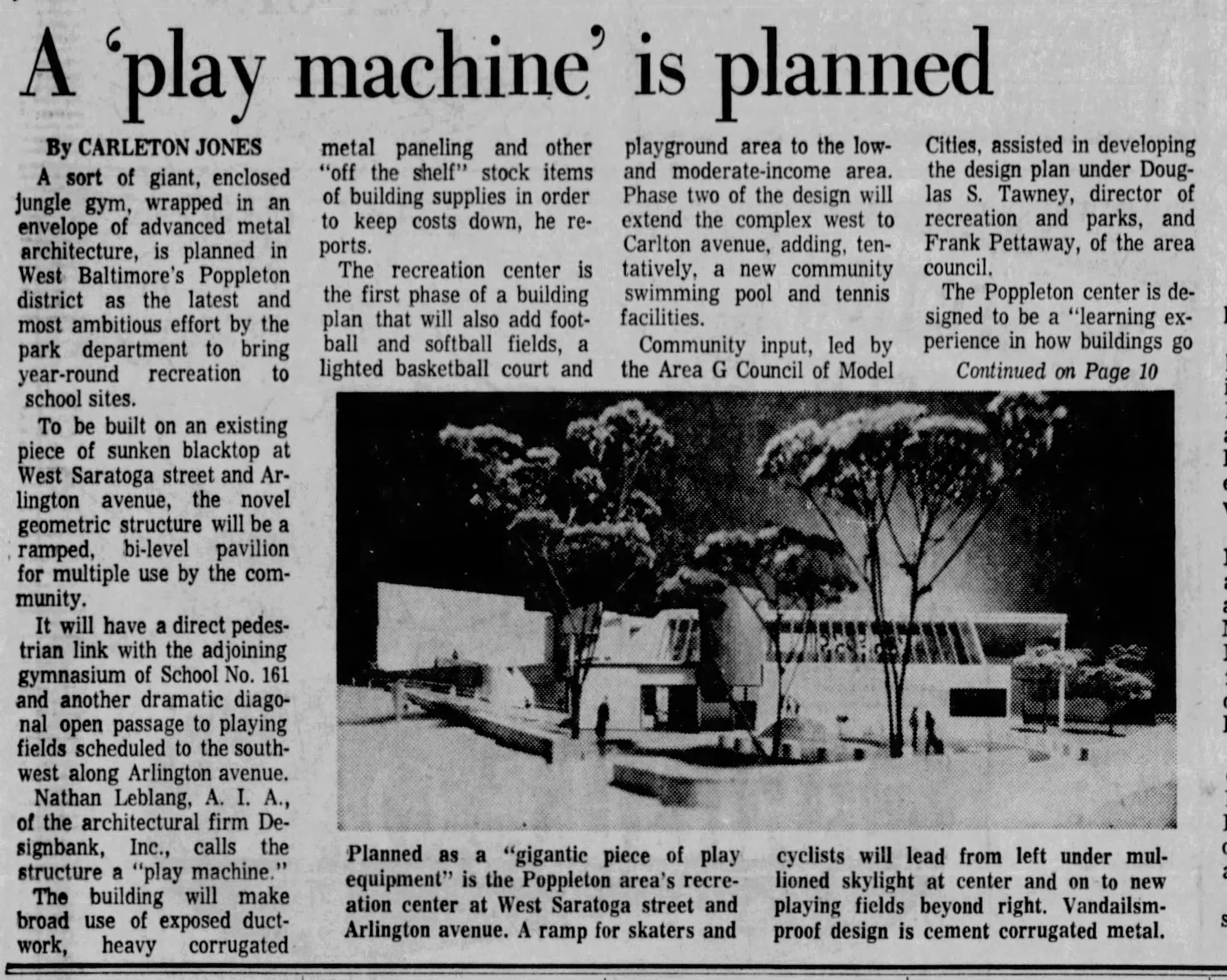

1976

The Greater Model Community Recreation Center opens, aka Poppleton Recreation Center. (Baltimore Sun)

1979

The Franklin-Mulberry Highway, aka the “Highway to Nowhere,” was completed, cutting Poppleton off from other neighborhoods to its north. (Baltimore Sun)

In the 1960s and ‘70s, the government made room for the highway by using eminent domain to take and demolish 971 homes and 62 businesses, displacing around 1,500 people.

West Baltimore (Edmonson Ave) before the construction of the 2.3-mile "Highway to Nowhere".

“[The recognition] means a lot to me after so much demolition in Poppleton that we managed to preserve this building that many thought wasn't worth saving. Even some of the Poppleton residents thought replacing it was best. This should stand as a message to our city leaders on the value of preservation in our neighborhoods.”

— Sonia Eaddy, Community Activist and Sarah Ann Street Homeowner